Surviving Anti-Asian Violence in an Anti-Black World

When the national media turned its eye to a growing wave of pandemic-intensified, anti-Asian attacks across the country, including the January 28 murder of 84-year-old Mr. Vicha Ratanapakdee, as well as other attacks against elderly Asian Americans around the weeks leading up to the Lunar New Year, I began to trace the social media and other media responses of my fellow Asian American intelligentsia. I had known already, on the ground, that volunteer groups and progressive organizations were putting together foot-patrol and chaperone teams, in addition to de-escalation, bystander-intervention, and self-defense trainings, and that their activist discourse had no time for the silly yet dangerous game of self-doubt and self-gaslighting regarding whether such violence was definable as properly “racist” or not.

It has become clear in 2021 that despite all of the recent liberal chatter surrounding “racial reckonings,” there is no way, still, to talk about anti-Asian violence as structural and affected rather than individuated and intentional. In a historical moment in which mainstream American culture has begun to thematize anti-Black racism and violence as properly structural, more than fifty years after Kwame Ture and Charles Hamilton introduced the phrase “institutional racism” to our lexicon, another lethal manifestation of white supremacy, anti-Asian violence, is currently held to the antiquated standards of individuated intention.

Yet if you looked at the responses of the Asian American “race studies” professoriate that one might group together loosely as my racial and professional group’s sanctified category of “public intellectual,” you would see zero mention of the victims’ pain or suffering, not until after the March 16 murders of six Asian American women (plus two others) by a white gunman in the Atlanta metro area. Prior to that, everyone in this cadre of educational attainment and class privilege, whose very vocation, I argue, includes the work of explicating issues of racism, violence, history, inequity, and injustice, to ourselves and to the larger public, was consistently silent on the violent terror, including murder, of some of the most vulnerable Asian Americans in our society. With few exceptions, not until after the gruesome, unspeakable bloodshed of March 16 did the likes of my group care to even name the victims of this pandemic-intensified onslaught of racist violence.

The primary reason here for such silence was that some of the violent offenders during this wave have been African American, including the person who murdered Mr. Ratanapakdee in broad daylight in San Francisco. The race of the murderer occluded the moral and political clarity of a dominant white-liberal-defined racial optics that, even for some Asian American experts on these topics, has made nonwhite life grievable only when the offender is white. The response, over and over again, from the Asian American intelligentsia at that time was to declare our solidarity, strangely enough, with white-defined notions of antiracism, proffering the reflexive tendency to begin not from the pain and suffering — or, again, even the names — of Asian American victims but rather from the propagandistic notion that Asian Americans are presumed, somehow preternaturally, to desire anti-Black violence through increased policing.

For instance, here is a quick snapshot of the evolution of the responses from Cathy Park Hong, poetry professor at Rutgers and author of the 2020 bestseller, Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning:

Notice that in February, the immediate lexical pivot is toward “BIPOC struggle” rather than the fact of anti-Asian murder. By early March, she is explicitly foreclosing the possibility that Black Americans and Korean Americans might actually know each other better than white people do. On March 17, at last, like everyone else, she is enraged, demanding to know the names of victims.

In the pages of the New York Times, it fell upon the journalist Jorge Ramos, on March 5th, to name, for the first time, Mr. Ratanapakdee, again, who was murdered on January 28th:

Some three weeks prior, over Lunar New Year weekend, the Times published an op-ed by Viet Thanh Nguyen, Pulitzer Prize-winning author and professor at the University of Southern California, whom I and many others consider the dean of all Asian American progressive intellectuals, about how much he enjoys teaching class on Zoom. This was well after other national media outlets had begun attending to anti-Asian terror and violence, and about one week after the Asian American actors Daniel Wu and Daniel Dae Kim began their speaking tour on the national media circuit:

Even in alternative media: there was an astonishing claim from the local outlet The Oaklandside in early February, here amplified by Nguyen, that centers the question of whether an attack on a 91-year-old Asian American was, in fact, “racially motivated”:

While the politics of the authors, Momo Chang and Darwin Bond Graham, is admirable, drawing attention to the economic desperation of some of the most severely neglected and victimized communities in Oakland—and cautioning and fighting against augmenting the police state—even that piece requires and propagates the central idea that anti-Asian violence can only be understood through the lens of individuated malice and intention. Anti-Asian violence here was reduced to “crimes of opportunity.”

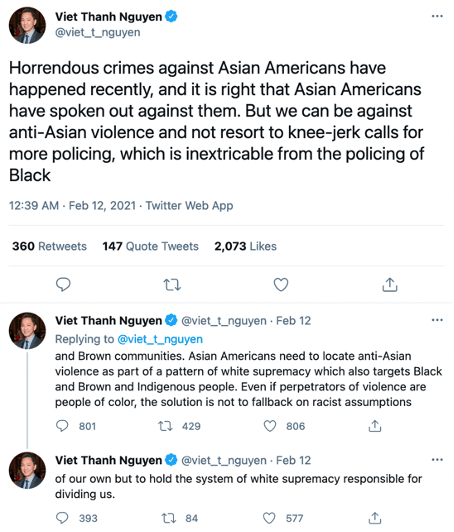

And then here is Nguyen in the same week as his Times op-ed, pivoting immediately from “horrendous crimes” to some specter of Asian American desire for increased anti-Black violence through more policing:

To be clear, to the best of my knowledge, there were no mass-scale “knee-jerk calls for more policing” from the affected communities. I understand that Nguyen here is responding to the entire breadth of political response articulated on Twitter, but consider how quickly his attention turns to “a pattern of white supremacy” from the specific focus on pandemic-intensified anti-Asian violence. I would contend that this response actually obfuscates how anti-Asian violence is a direct and singular expression of anti-Blackness, and that we do a disservice to the people-of-color solidarity implicitly desired in this statement if we do not attend to this particularity. I would also contend that within these reflexive pronouncements from Hong and Nguyen, among others, lurks a cognate condescension to both African Americans and Asian Americans that we would not be able to detect the difference between individual violent offenders and systemic anti-Black racism, the latter of which, as currently understood in a public framework and as exemplified through these posts, does not and cannot account for Asian American victims.

To be clear, I am not and have not been under the impression that a vanguard class of Asian American MFAs and PhDs would protect the entirety of our racial group through Twitter or through Atlantic articles. But it has been unbelievably sad to me that the group to which I belong has provided neither conceptual clarity nor moral authority to a situation that, even despite the relative protections of the professional-managerial class, affects us so immediately. As Mr. Ratanapakdee’s face reminds me of my own grandfathers,’ it was alarming to me that people with very similar privileges, educations, and politics to mine have been complicit in the foreclosure of structural understandings and public ways both to grieve Mr. Ratanapakdee’s death and to protest the racial injustice of his murder.

Against this dominant anemic understanding of anti-Blackness, I argue that a proper understanding of racial ontology in an anti-Black world would mean that anti-Black violence actually includes the vulnerability to harm of low-income and otherwise vulnerable Asian Americans.

In other words, there is no current public framework to discuss anti-Asian violence within an anti-Black world. Toward that framework, I submit to you today that anti-Asian violence must be understood as an effect and feature of anti-Blackness, a constitutive feature of an anti-Black world that requires all manner of racist violence for it to house racial capitalism. I will then briefly discuss the political liabilities of this epistemic gap in our intellectual culture, contextualizing it within the academic-theoretical regime of Asian American Studies, whose signature affect is shame and whose theoretical ambition has been defined by willed self-erasure. Then I will discuss how the academic abandonment of the identity and group-concept of “Asian American” has, in my view, directly contributed to this political morass, as this is the feature shared by both the academic voices as well as the reactionary ones in Asian America. Finally, I will close with my own AfroAsian and Black-feminist prognostication toward a proper understanding of how we comprehend and respond to anti-Asian violence.

Anti-Black and Anti-Asian Propaganda

Accompanying the recent boom in Asian American cultural and political representation has been the highest-ever visibility of Asian American expertise on race, whose nominally progressive or even radical antiracism is attached to access to giant public megaphones. Along with many of my family and friends, I have been gladdened by the proliferation of thoughtful expositions and reflections in the last two weeks. As the Korean American hip-hop legend Jonathan Park, a.k.a. Dumbfoundead, tweeted that weekend: “Welcome, born again Asians, better late than never.” Until two weeks ago, while familiar tropes of diseased yellow hordes were rehearsed by the ruling elite and many others for the past year, the Asian American intelligentsia had no sense of Asian American solidarity to offer as a public-facing response to, among countless other harms and atrocities, the murder of Mr. Ratanapakdee. Consider the cruelty of the timing of Asian American intellectual silence and self-erasure that coincides with the current onslaught of anti-Asian sentiment, bigotry, and violence during the coronavirus pandemic.

Model-minority mirage, myth, and propaganda — and often my own class’s complicity in cosigning or falling prey to them — have now fully naturalized the notion that Asian Americans and African Americans are inherently in opposition. This notion is historically, and at present, false. The notion that Asian Americans, seemingly across all class strata, naturally despise Black folks—because of internalized white supremacy, perceived economic competition, or both—is one vicious form of what Michael Omi and Howard Winant famously argue as the “racial project” of “making people up” through rendering racial ideology a part of our Gramscian “common sense.” This ideological naturalization is simply a neoliberal update to the American racial project devised to divide people of color and ultimately all of us.

Generally speaking, it is true that Asian American thinkers have failed to claim our own voice through our own racialized status within an anti-Black world. A historically determined desire for white liberal approval has made some of us truly believe that we are protected under white supremacy. This notion is also historically, and at present, false. Ironically, even the contemporary language of antiracism is now mobilized by some academically comfortable Asian Americans to side with elites rather than to defend the most vulnerable Asian Americans in our society.

To echo Claire Jean Kim’s idioms for the Asian American presence within a system she calls “racial triangulation,” some economically comfortable Asian Americans are choosing permanently inferior yet “relatively valorized” status in a world constituted by anti-Blackness:

It is as if the “civic ostracism” portion of Kim’s thesis has been maligned by our intellectual elites, and that our status as an “immutably foreign” Other, which makes all of us vulnerable to racist violence, especially in eras defined by xenophobic sentiment in general and Sinophobia in particular, has been lost on us as we continue doing our part on behalf of the white-supremacist work of naturalizing a presumptive division between Blacks and Asians in America.

Once this naturalized division is the starting-point for analysis, a white-supremacist notion of people-of-color intramural racism takes over our discourse, and our uniquely Asian American voice gets scripted toward what Jared Ball calls “message force multiplication.” Our recent language reveals how fundamentally committed we have been to the spurious idea that Asian Americans are complicit in anti-Black racism if 1) we demand justice for Mr. Ratanapakdee’s murder and 2) name that murder accurately as racist violence. Consider, for instance, how silly a pronouncement it is to declare first, as so many of us tend to do these days, that “anti-Black racism is ‘real’ in Asian American communities.” Even the consistently progressive Asian Americans Advancing Justice Atlanta promoted *this* workshop, just days after the March 16 murders, that framed Asian American anti-Black racism as a central issue:

As a researcher in anti-Blackness, allow me to respond in unequivocal terms: Where isn’t anti-Black racism “real” in an anti-Black world? Asian American intellectuals and organizations now speak as if anti-Blackness needed to hear our recognition of its realness, of its ontological animation, as if it cares, and as if our recognition of it would stop its violence. We speak that pronouncement as if Asian American communities are more anti-Black than white ones, which is absurd on its face given the historical linkages between all expressions of white supremacy in an anti-Black world, beginning from the racialized class exploitation that pits the most desperate and vulnerable Black folks in our society against precarious Asian immigrants often rendered the middleman minority beneath the petite bourgeoisie. It is more than strange that anti-Black racism in Asian America has become a central trope during this period of our heightened vulnerability to violence, and rather than defense against Twitter racists, I argue that this racist trope is being expressed, even by some of our own, because we have not had the courage to articulate antiracist cultural and political frameworks of our own in this moment.

I would like to observe that in my own life, here in South Carolina, the first person to reach out to me on the morning of March 17 was my friend Dr. Jermaine Johnson, state house representative for District 80 and the first African American to hold this seat. He was on his way to the state legislature that morning to fight against the open-carry bill:

As Dr. Johnson tweeted, the traumatic experience of racist violence provides an opportunity, as tragic as such opportunity is, to think together about what minoritized groups have in common, and just this tweet, I would argue, gives lie to the scandalous, propagandistic notion that Black Americans and Asian Americans are related primarily by antagonism and misapprehension.

Now, allow me a brief historical and personal reflection on the political economy of the American racial project since 1965, the year that the anti-Asian immigration quotas were, at last, abolished. Even as 1965 would, in turn, start to skew the Asian American population, in the words of Christopher Fan, as the country’s most “occupationally concentrated,” and even if it is the case that the political economy of Asian immigration has aligned the majority of the most visible and privileged Asian Americans with the white well-to-do, our common-sense framework for understanding our racial consciousness misses key components of what Asian American professional-managerial-class experiences look like.

So for instance, it is certainly the case that Asian Americans in the corporate sector, including in academia, are privy to the anti-Black sentiments, remarks, and hostilities of our white peers in ways by and large kept secret from our African American counterparts. This has been an abiding feature of my own life since I arrived in this country at the age of six. It has been an unceasing and predictable psychic violence that has actually gotten worse as I develop my academic career and become further siloed into academicization.

White colleagues will comment to me about Black colleagues or students or staff or other everyday people in ways that presume my alliance with their racist anti-Black assumptions. This goes on in my life despite my professional positioning as a professor of African American Studies and as someone affiliated with some of the best-known Black scholars of our day, including my friends in this room. Having lived in liberal college towns most of my life, one irony I have traced—again, since the age of six—is that these views and presumptions come from white people who consider themselves virtuous, educated, woke, and above racism altogether, even though by the sociological data, as Adolph Reed always reminds us, it is they who live the most segregated lives of anyone in the United States. Rather than the racist presumption that Asian Americans in these situations simply mimic and reproduce this anti-Black racism, it occurs to me that we need a much more complex framework for how this particular phenomenon affects Asian American consciousness regarding anti-Blackness. So, for instance, if a white person spews anti-Black sentiment to an Asian American because of their racist presumption that Asian Americans are “white adjacent” or “honorary white” or whatever, then why do we not call this what it is: anti-Asian racism?

In this way, it seems to me that the now common-sense presumption that Asian Americans function as preternaturally anti-Black needs to be exfoliated against the counternarrative of the surplus of both anti-Black and anti-Asian racism that saturates the professional (and other social) experiences of even the elite Asian Americans. Relatedly, there has always been a racist presumption that even in the professional-managerial class, Asian Americans and African Americans have little in common and that the model minority myth drives a wedge between them. Yet since it is the case that the Black segment of the professional-managerial class has quadrupled in size between 1965 and 2000, parallel to the occupational concentration of their Asian American counterparts, there are clear sociological connections between their experiences, especially in terms of opportunity structures, capital access, non-white professional communities and networks, in addition to workplace racism, the lack of established professional pipelines, and the precarity and pressures of wealth accumulation. I think of my own POC staff and faculty friends, predominantly Black and Asian American, from the tony private high school in west Los Angeles where I taught for a year before my current job, and how deeply we remain bonded from our shared experiences professionally as well as extramurally. Even while we were catering largely to extreme wealth, there was more pro-Black consciousness in that space than any public or private university English department I have worked in.

This is all to say that we also speak as if we have not reckoned with the Ontological Turn in Black Studies, specifically the theoretical tendency and field of thought known as Afropessimism that has singlehandedly amplified the precise notion that anti-Blackness is axiomatic to reality itself. Once white-liberal vacuity takes the place of an organic analytic derived from shared people-of-color consciousness, our response can become distorted as well, as people of all colors begin to believe that African Americans cannot see the difference between shallow white-defined gestures of allyship and true shared integrity in the demand for justice. The Black Radical Tradition, for one, has always required such integrity. And it is, again, simply a matter of naturalized anti-Blackness that makes us think that Black folks can’t easily discern the difference between lethal anti-Asian violence and systemic anti-Black racism.

Anti-Blackness does not need anyone to be aware of it. Anti-Blackness structures reality itself. Anti-Blackness, in addition to its constitutive violence first and foremost to Black people, also expresses itself to other racialized people. Further still, consider just how many Asian Americans, already affected by the threat and reality of racial violence against ourselves, began navigating and addressing anti-Blackness to impressive effect during the pandemic: in September 2020, 69% of Asian Americans reported supporting Black Lives Matter, in contrast to 55% of the country overall. The general intelligence is rich—and appears, in fact, to be growing, against the grain of false narratives regarding perpetual, irresolvable Black-Asian conflict and administered white-Asian proximity.

Echoing the chorus, Vince Schleitwiler sagely reminds us that renewed Asian American political consciousness ought to begin from solidarity with the Movement for Black Lives, since we only know ourselves as “Asian American” in the first place from this historical alliance: “As the first Asian American movement demonstrated, the development of such a consciousness cannot end anti-Blackness in itself. But it can remind us that no one, including Asian Americans, will be free until Black people are free, and so solidarity against anti-Blackness must be fundamental to our collective self-definition. Because without it, we wouldn’t even know who we are.” What it means for Asian Americans to know ourselves—and to love ourselves—is to align our unique racial being with Blackness in an anti-Black world. Yet such alignment has been precluded by the cultural and political backdrop I have sketched here, in which the default tendency of thought has been, particularly for elite and aspiring Asian Americans, to mimic the false notion that our group is by default, by self-hating pathology, white-desiring and white-allied.

Other Lovings

For roughly the past twenty years, Asian American discourse, specifically in elite academia, has been defined by its preoccupation with self-negation, suggesting the outmodedness of the banner “Asian American” altogether. In my forthcoming book, Other Lovings, I rebut this academic assumption of Asian Americanness as a container of historical and political failure. Critical discourse has, more or less, signaled the triumph of Asian American self-erasure, and the neoliberal era has made an easy path for fancy explications of “Asian American” as an empty and meaningless signifier within the world of literary and cultural theory. For instance, the “racial melancholia” thesis argues that Asian American psychic life is founded upon lack and lovelessness, not only as periodic feeling and passing mood but as the constitutive structure of our racial experience. An index of the crisis in Asian American discourse is that well-intentioned scholars of immense privilege have ontologized a false presumption regarding the lack of love in order to make the scandalous assertion that Sigmund Freud’s theory of melancholia constitutes the Asian American person, arguing that Asian-ness in America is founded upon the “losses, disappointments, and failures” generalizable to post-1965 Asian American life, concatenating the model minority mirage to the affective structure of racial experience.

According to its theorists, David Eng and Shinhee Han, racial melancholia reveals both whiteness’s absolute power as well as the subsequent framework for our psychic constitution: as not only tethered to and interpellated by whiteness, but as always already its constitutive, negative other, which functions to pathologically seize up any liberatory possibility while also reducing Asian American being, in effect, to a form of narcissistic attachment. This model insists that we view Asian American experience through the lens of racial whiteness only and first—through masochistic receipt of white supremacy’s affective vectors—thereby leaving little hope for the possibility of an Asian American happily and/or stealthily out of sight from the white gaze, having cast our lot elsewhere.

The assumption of Asian American subjectivity as nothingness itself, not to mention the repeated assertion of “Asian American” as a putatively useless abstraction signifying something called a “subjectless discourse,” has been made through a full gamut of recent methods in academic theory—including literary formalism (Colleen Lye), political economy (Mark Chiang), deconstruction (Kandice Chuh), and, of course, psychoanalysis (Anne Cheng, in addition to Eng and Han). Asian American discourse has thus converged in the new millennium to normalize the notion that “Asian American” means nothing at all. In turn, should we be at all surprised when during this period of heightened hostility and violence that we have no intellectual leadership to speak of?

Relatedly, two of the most visible Asian American popular writers are also fixated on the notion that we don’t exist at all.

Jay Caspian Kang, writing in the New York Times in August 2017, asserts that “‘Asian-American’ is a mostly meaningless term. Nobody grows up speaking Asian-American, nobody sits down to Asian-American food with their Asian-American parents and nobody goes on pilgrimages back to their motherland of Asian America.” Wesley Yang declares in March 2018 that “there has always been something faintly ludicrous about the ‘Asian-American’ identity. All races are, to varying degrees, artificial constructs. The ‘Asian-American’ identity is an artificial construct that scarcely anyone claims.”

Now please tell me that this self-erasure—asserted both by academic researchers and popular writers—isn’t directly linked to our relative silence in 2021. To add further insult to our racial injury, consider that the nation’s newspapers of record published in the days following March 16 racist articles regarding how Asian immigrant cultures emphasize silence, “keeping our heads down,” and other pathologized notions of cultural and political passivity. Rather than resilience amidst racist hostility and a generations-long critique of individualism and individuation, even the perceptions of our historical responses to lethal violence were used against us immediately. In 2021, if you were to absorb the general status of Asian American living only through academic and liberal media quarters, then you would surmise that we possess no identity—no “we”—at all.

Thankfully, on the ground, the intensifying anti-Asian violence has already led to what Yen Le Espiritu, in the wake of the Los Angeles riots of 1992, called a pan-Asian “reactive solidarity”: “While political benefits certainly promote pan-Asian organization, it is anti-Asian violence that has drawn the largest pan-Asian support. Because the public does not usually distinguish among Asian subgroups, anti-Asian violence concerns the entire group—cross-cutting class, cultural, and generational divisions. Therefore, regardless of one’s ethnic affiliation, anti-Asian violence requires counter-organization at the pan-Asian level.”

To my estimation, despite all of the academic chatter about the incoherence or nonexistence of our racial group, it is clear that reactive solidarity is alive and well during this pandemic-intensified wave of anti-Asian sentiment and violence. It is also clear that “Asian American” as an identity banner is enjoying a resurgence on the ground, coinciding with the latest iteration of Black Lives Matter, as mentioned by Schleitwiler, in which it is mine and his hope that we understand the pro-Black politics built into the very concept of “Asian American.” Again, it could be considered the vocational responsibility of our present-day intelligentsia to provide this proper people-of-color-consciousness origin of the term “Asian American,” which at its root, is neither simply census category nor meaningless signifier, but rather an intramural pan-Asian identity and an extramural people-of-color identity devised by childhood survivors of Japanese American internment as they became radical college students in the late 1960s.

In the same era in which Emma Gee and Yuji Ichioka coined the term “Asian American” in service to themselves and to pro-Black, Third World consciousness, both the political economy of immigration and the administration of the model minority stereotype began their work to dim the prospects for the growth of such historical consciousness. The originary claim to “Asian American” is simultaneously to have cast our lot with Black liberation struggle, yet in the intervening neoliberal order since, the regime of racial triangulation and its attendant anti-Black strategy of the model minority mirage have occluded this fact.

The writers Frank Chin and Jeffrey Paul Chan, having understood this historical tension in real time, proclaim in their 1971 treatise “Racist Love” that “if the system works, the stereotypes assigned to the various races are accepted by the races themselves as reality, as fact, and racist love reigns. The minority’s reaction to racist policy is acceptance and apparent satisfaction. Order is kept, the world turns without a peep from any nonwhite. One measure of the success of white racism is the silence of that race and the amount of white energy necessary to maintain or increase that silence.” Frank Chin and Jeffrey Chan here accurately predict the full saturation of the model minority stereotype that turns “Asian American” into a cipher of what they call racist love, which is a love that our racial melancholia theorists, some fifty years later, have embraced and imposed as something to desire in return. Chin and Chan warn against casting our lot with the desire for white acceptance and the submission to racist love. Here, then, we have the historical juxtaposition of “Asian American” and “model minority” appearing as a matter of our loving and of our surviving, toward either the collective being of Black liberation, which includes us, or the embrace of an oppressive white supremacist love.

Among our group, the signifier “Asian American” has thus been left mainly in the hands of the old-fashioned faithful, who remain committed to the notion of AfroAsian collaboration and people-of-color consciousness, not to mention inter-ethnic solidarity under the banner of phenotypic similarity, which, to echo Yen Le Espiritu, historically surges during periods of heightened xenophobia and violence. And yet, it isn’t only the Asian American faithful who have done and said this. In the 2000 preface to Cedric Robinson’s classic book, Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition, Robin D.G. Kelley poses the following question: “What do we make of radicals who are neither [B]lack nor white, militants such as Harlem’s Yuri Kochiyama or Detroit’s Grace Lee Boggs or the many South Asians in England and elsewhere who cast their lot with the Black Radical Tradition?”

This question, posed at the turn of this century, has yet to be taken up systematically by the field-defining Ontological Turn in Black Studies, which was itself augured by Robinson’s book, particularly by way of its middle chapter, titled “The Nature of the Black Radical Tradition,” where Robinson sounds the clarion call for “the continuing development of a collective consciousness informed by historical struggles for liberation and motivated by the shared sense of obligation to preserve the collective being, the ontological totality.” I submit that the significance of Kelley’s query has only increased since the development of the study of Blackness and anti-Blackness through an explicitly ontological framework in the new millennium.

Kelley’s question, on the one hand, delineates the epistemic boundaries of Robinson’s notion of the Tradition by posing the rhetorical question of the history of Asian American activists’ and thinkers’ resistance to racial capitalism by way of Black radical politics. Yet given the ontological merit of the Tradition, held within the notion of “collective being” and as has been expounded recently by Fred Moten, Tendayi Sithole, and Kelley himself, this query also illuminates and exemplifies the Black Radical Tradition’s ontological openness. On this view, Blackness’s ontological resistance to the notion of settled enclosure is indeed what constitutes its “totality,” brought into historical relief, in no insignificant part, by the love of Blackness and for Black people that flowed through, among countless others, Yuri Kochiyama and Grace Lee Boggs. Ontological Blackness, it could be said, encompasses Asian American resistance as a constitutive feature. Thus, ironically, the academic triumph of an Asian American installation of nothingness has occurred while the Black Radical Tradition installed a fullness and openness to the concept of Blackness, a fullness and openness that encompasses all victims of the racist violence necessitated by racial capitalism.

Another irony of this moment of anti-Asian violence and terror is that it overlaps with an unprecedented boom in Asian American cultural and political representation. While Asian American intellectuals were busy theorizing ourselves away—to the point that there was neither “our” or “selves” to begin with—Asian American representation in the culture industry reached an all-time high. The actor Steven Yeun, promoting the Korean American film Minari (미나리), told Kang in the New York Times Magazine in February: “Sometimes I wonder if the Asian American experience is what it’s like when you’re thinking about everyone else, but nobody else is thinking about you.” (And you know the New York Times is not thinking about us because it continues to use that dumb and outmoded hyphen.) In this bizarre way, our cultural workers, even the celebrity class, seem to be doing a better job than our intellectuals of not only speaking out but of describing our unique racialized position. Yeun’s is an Asian American phenomenology that may at first seem to echo W. E. B. Du Bois and Frantz Fanon, but that centers as its starting-point neglect and dereliction, rather than Du Bois’ pity and contempt or Fanon’s interpellation and derogation. And now, we are living in a moment in which pity, contempt, interpellation, and death are also pronounced elements of this Asian American phenomenological content.

Mother Lovings

In this way, perhaps it is fair to say that the Asian American intelligentsia has much to learn from the Black Radical Tradition, beginning, as I have argued, from how we even congregate, identify, and imagine our “we” and “us.” Allow me one more entry-point to the openness of this Tradition. One constitutive thing that Asian American culture shares with African American culture is the originary care, touch, and affectability handed down by the mother. This brings me, finally, to the murders of March 16:

The maternal is handed in and through us, which effect gets further amplified within the protective environments required to survive a racially hostile and violent country. Such maternal care and protection get amplified still further, unsurprisingly, when you come from a single mother, as Kim Hyun Jung was, and as Randy and Eric Kim do. And as I do. Randy shares that, “She wasn’t just my mother. She was my friend,” and that “she was a single mother of two kids who dedicated her whole life to raising them.”

I think we ought to provide a framework for how to assess and to grieve the Asian American and Korean American particularity of this utterance. We need to make a space for it. The predictable pathologizing of single mothers is one calling-card of white supremacist discourse, yet the best features of the Black Radical Tradition—radical Black feminism, Afropessimism, and Black Male Studies—have provided a language for how the symbolic presence of the Black maternal is always dangerously misread, illegible to violent white patriarchal norms, then turned around on both mothers-and-daughters and fathers-and-sons as a racially-violent “tangle of pathology.” Consider the sheriff who had the gall to characterize the murderer’s “bad day” and “sex addiction.” Those words actually left his mouth. These are not surprising items to be conveyed from the alternate reality of white supremacy, and yet they were traumatizing to hear.

This is our actual reality—a reality felt in the bones of every Asian immigrant and every Korean American, to be sure, as described by my own kin: “All I can think is her last thoughts would’ve been worrying about her sons, who have no other family here.” I submit that the last two weeks have reminded me how my own cultural configuration rhymes with aspects of the Black maternal that I study and teach, despite very different social histories and political conditions. If this maternal emphasis is the basis for Black culture and Blackness, as Hortense Spillers and Fred Moten teach us, and Korean and other Asian formations possess similar or parallel maternality, then why don’t we conceptualize Asian American being and culture in this way?

The sense of moral and political integrity that Black Studies at its best has commanded is something that the Asian American intelligentsia does not, at the moment, even attempt. If the Asian American intelligentsia, privileged with access to every academic advantage the western world has ever afforded, cannot make sense of this moment of anti-Asian violence—attending consistently to our victims and claiming them ours, regardless of the racial optics of individual cases but rather toward a systematic understanding devoid of the desire to look deep into the heart of hearts of violent offenders—well, then, what is our function—to ourselves, to our students, as well as to the larger public?

As a corollary, if the violence of racist terror won’t cohere the banner of “Asian American”—an identity that has been critiqued to full negation by academic discourse with special verve in the twenty-first century—then what will? I would suggest we begin by considering the simultaneously preservative and transgressive function of the maternal bonds found within reactive solidarity. I applaud the recent work by my colleagues that has appeared since March 16, but I fear this period has already been defined by our relative neglect and silence.

Seulghee Lee is Assistant Professor of African American Studies and English at the University of South Carolina.

For their generous exchanges as I developed this piece, I would like to thank Alvin J. Henry, Vivian L. Huang, Manya Lempert, Rosa A. Martínez, Fred Moten, Ismail Muhammad, Paul Nadal, Emily Yoon Perez, Scott Trafton, and Sunny Xiang. Here is a recording of the March 31, 2021 talk.